Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Directed by Kim Ki-duk.

Starring Young-soo Oh, Kim Ki-duk, Young-min Kim, Jae-kyeong Seo, Yeo-jin Ha, and John-ho Kim.

Directed by Bae Yong-Kyun.

Starring Lee Pan-yong, Sin Won-sop, and Yi Pan-Yong.

Set entirely on and around a floating temple (a set built for the movie on an artificial lake built about 200 years ago, to be specific), Kim Ki-duk’s 2003 feature Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring is a beautifully crafted but frustratingly artificial tale of one man’s life told in five chapters. The most disappointing aspect of Spring is how amazingly beautiful it is — disappointing because the several gorgeously photographed, languorous shots of the valley around the temple on the lake, sublime music, and mostly solid, understated performances with minimal dialogue make for exactly the right tone for the kind of film this aspires to be — yet its story falls short.

The film begins innocently enough — in “Spring,” of course — with a charming but troubling story wherein Child Monk (Jong-ho Kim) ties stones to a fish, a frog and a snake. Old Monk (the enchanting Young-soo Oh) is disappointed in him, so he ties a large stone to the child as he sleeps that night and says that he’ll only remove it once the boy has found the three animals and released them, telling the boy that if any of the animals are dead, he will carry the stone with him in his heart for the rest of his life. As he finds them, he discovers that the fish and the snake have died and begins to cry. Even as I was moved by the boy’s tears, it troubled me that the Master placed more importance on the boy’s lesson than the lives of the animals, a choice that — although I am neither a Buddhist nor a scholar of Buddhism — struck me as rather inauthentic.

In “Summer,” a sick girl (Yeo-jin Ha) is brought to the temple by her mother. Boy Monk (Jae-kyeong Seo), probably in his late teens, is obviously sexually entranced by her and, after placing a blanket over her as she sleeps, tries to cop a cheap feel off her. She slaps him, but — since this is a movie — soon enough they are having sex. Health restored by the healing power of sex, she is soon sent home and, that night, Young Adult Monk sneaks away to follow her to the world in spite of his master’s warning that lust begets possessiveness, which in turn begets “intent to murder” — a line that is obviously foreshadowing because of its outright absurdity.

In “Fall” (“Autumn,” as the subtitles call it), our protagonist, now played by Young-min Kim, is now 30. The old monk learns from the timeworn movie cliché of newspaper used to wrap a fish that he has killed his wife (presumably the girl from “Summer”) in a jealous rage and fled from the law. Upon discovering his protégé has returned to the temple and is about to commit suicide with the knife he apparently used to kill his wife (it is, ludicrously, still encrusted with her blood), the old monk beats Young Adult Monk with a cane, and strings him up inside the temple while he writes the Prajna Paramita Sutra on the outdoor deck of the temple with his cat’s tail. He then instructs Young Adult Monk to carve out the characters with his knife. (Though we are not benefited with a translation, the Prajna Paramita Sutra is known as “the highest mantra, destroyer of all suffering, the incorruptible truth,” and the Sutra itself roughly translates as “Gone, gone, gone to the other shore gone. Enlightenment hail.”) While he carves out the symbols, the two monks are shortly joined by two police detectives (Dae-han Ji and Min Choi), who at first watch Young Adult Monk carving through the night and later help complete it for him after he has passed out from exhaustion before taking him off to face justice. As he wakes up and sees the Sutra, now painted by the Master and the two detectives, and we see enlightenment suddenly wash over Young Adult Monk’s face. Though well acted, it still seemed just a bit too easy.

After the younger monk is lead away by the police, the Master builds a pyre on the boat, covers his eyes, ears, and mouth with pieces of paper with the symbol for “shut” drawn on them (as the younger monk had done before his aborted suicide attempt), and ends his own life. It is significant to note here that suicide has actually been praised in some early Buddhist texts, but “the Buddha’s praise of the suicides [was] not based on the fact that they were in terminal states, but rather that their minds were selfless, desireless, and enlightened at the moments of their passing” (“Buddhist Views of Suicide and Euthanasia” by Carl B. Becker); it is reasonable to assume, then, that the old monk’s suicide is not motivated by any feeling that he has failed in teaching his apprentice — rather that he has completed his task by passing enlightenment on to his apprentice, a point that may be lost on viewers wholly unfamiliar with Buddhism.

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring

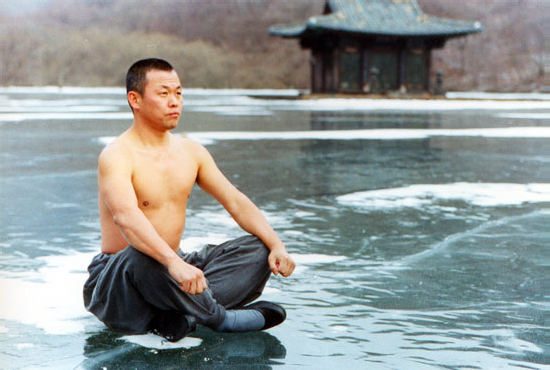

In “Winter,” we assume Adult Monk has spent some time in prison, because he is now played by the director (who is 44). As he returns to the temple, he finds the Old Monk’s few possessions laid out as they’d conscientiously been left for him and a snake resting on the neatly folded robes (which, incidentally, should be hibernating during this season). He digs into the ice of the submerged boat and retrieves Old Monk’s teeth to place in a Buddha he carves out of ice and, after finding a book of martial arts stances, the Adult Monk meditates at various picturesque locales around the temple, giving us the overall impression that the monk is finalizing his own training.

Some time later, a veiled woman (Ji-a Park) walks out across the ice, prays and sobs with equal enthusiasm, and leaves her baby with the monk at the temple. As she leaves, we are treated to the most ridiculous moment in the film when she falls through a slightly iced over hole the monk had carved in the ice to wash himself through the winter, and dies. Yes, seriously. I would like to think that the woman committed suicide, but the scene certainly did not seem staged that way; also, why would she hide her face if she had intended to kill herself after giving up her child? (The moralistic implications of this, and we can only assume there must be some, are especially disconcerting because we are not granted any insight into why the woman is giving up her child; is giving up her child for any reason, however grave, an offense deserving of death?)

The next morning, led to the hole by the baby who has seemingly telepathically divined that his mother has fallen through the ice at that spot, Adult Monk retrieves her body and looks at her face, which we don’t see. Subsequently, the monk takes a Buddha and a millstone, which he ties to himself, and climbs to the top of a nearby mountain to place them where the Buddha will overlook the lake. For a film with so little dialogue, it is almost impressive how heavy-handed the themes are addressed. For instance, as Adult Monk climbs the mountain, we are shown flashes of the animals he tied rocks to as a child, and in its brief coda, “… and Spring,” we get a glimpse of the baby, now several years older and played by the same boy who played out protagonist in the first sequence, cruelly beating on a turtle’s shell, just so that we don’t miss the symbolism of it all.

It is tempting to argue that Spring is a fable, thereby dismissing all of the films absurdities. The first vignette certainly lends itself to this interpretation, but the strongly Western-influenced story doesn’t permit its characters to act as the archetypes that this interpretation requires. At the same time, the film is too frequently absurd, too theatrical, to accept matter-of-factly, either. Perhaps it is this Western influence that bothered me so much. It transforms what apparently intends to be read as a tale of “natural renewal” (as J. R. Jones described it in his capsule review for the Reader) and enlightenment, which is central to Buddhism, into a trite tale of redemption through enlightenment — perhaps influenced by the fact that Ki-duk was raised as a Christian, not as a Buddhist.

Ultimately crossing the thin line between exquisitely simple to gratingly simplistic, Spring simply made me want to run home and re-watch Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?, a 1989 feature by Bae Young-kyun and a masterpiece which falls decidedly on the more preferable side of that line. With more than just a few similarities, it is difficult to imagine that Kim Ki-duk wasn’t influenced by the earlier film. Set largely around a temple in the mountains of South Korea, Bodhi-Dharma details the lives of an old monk, his younger monk apprentice, and the young orphan who lives with them over a short period of time. In an early sequence less effectively echoed by the first “Spring” chapter of Spring, the young orphan in Bodhi-Dharma throws rocks at two jays, injuring one. Out of guilt, he attempts to nurse it back to life but fails, and the jay’s mate watches him from a distance thereafter.

Yong-Kyun Bae is a primarily a painter. Aside from Bodhi-Dharma, he has made only one other film.

While Bodhi-Dharma may not immediately appear as well-photographed (its lower budget and a less-than-perfect transfer to DVD are to blame, not poor cinematography), it has equally beautiful imagery but is thankfully devoid of the cloying, heavy-handed contrivances that make the new film more palatable to the critics in this country, who seem to only want to watch the same redemption story recycled over and over again and have almost uniformly heaped praise on Spring.

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is the film equivalent of a Buddhist koan like the one that introduces the film: “To the disciple who asked about ‘Truth,’ without a word, he showed a flower.” Beautiful, subtle, and thought-provoking, Bodhi-Dharma opens before your eyes like a blossoming rose; Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring, on the other hand, is more like a silk rose: a “perfect” — but far less interesting — approximation of the real thing.

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring is currently playing at the Evanston Century 12/CineArts 6 and the Music Box.

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is available for rent from Facets, as well as GreenCine and Netflix.

(Originally published in Gapers Block on May 14, 2004. Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring is now available on DVD via Netflix. Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is available via Netflix Streaming with a different transfer — and a few minutes of additional footage — than the copy I reviewed. Multiplex readers will note that Bodhi-Dharma is one of Jason’s favorite movies, and it’s one of mine, as well, but I would advise you to be wide awake when you see it. Its glacial pace knocked me out the first four times I tried to watch it.)